Menopause, HRT & Cardiovascular Risk

Females have about a 10-year advantage over males when it comes to the onset of cardiovascular disease1.

On average, females present with heart attacks later in life.

Because of these facts, females are considered to be ‘lower risk’ when it comes to cardiovascular disease.

Which is true for many females.

Earlier in life.

However….

-

Cardiovascular disease is still the leading cause of death in females in most countries2.

-

30% of all heart attacks in females happen at less than 65 years of age3.

-

Not all females have that 10-year advantage.

Females are also at increased risk of other types of cardiovascular disease compared to males, most notably spontaneous coronary artery dissection and also stress cardiomyopathies.

So while, on average, females enjoy a delayed onset of cardiovascular disease compared to males, certain factors increase the risk of cardiovascular disease earlier in life for females.

Rates of cardiovascular disease have decreased considerably worldwide but, concerningly, have increased in females aged 35 to 544.

Cholesterol & Menopause

Familial hyperlipidemia (FH) is a genetic cholesterol disorder which impacts about 1:200 people.

Females with FH do not have the 10-year advantage we mentioned above and develop cardiovascular disease about 20 years earlier than females without FH5.

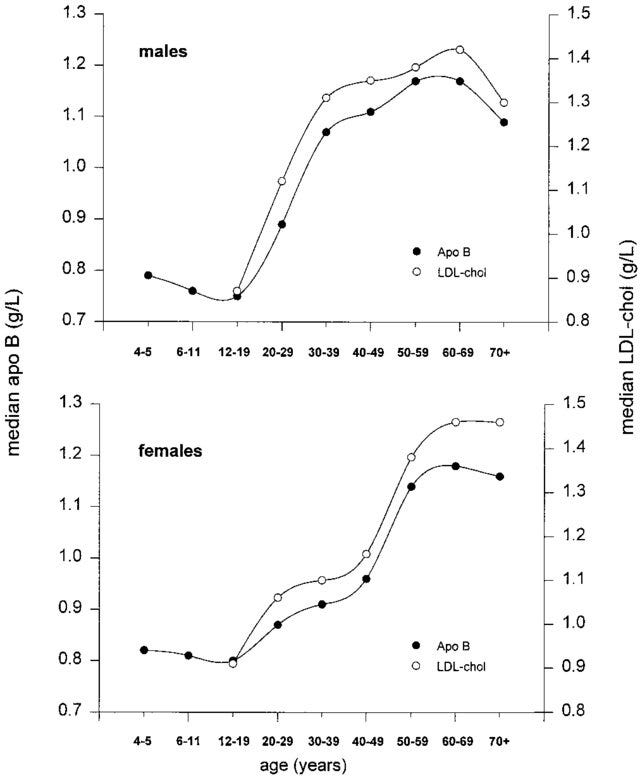

Males tend to have higher LDL cholesterol concentrations earlier in life which is one of the key reasons they develop cardiovascular disease earlier in life.

LDL cholesterol levels in females do rise, but usually later in life and also reach a higher peak6.

This rise in LDL cholesterol levels typically coincides with the onset of menopause in females.

Therefore, early menopause is associated with an earlier increase in LDL cholesterol levels and an increase in cardiovascular risk.

Females who go through menopause at less than 45 years of age are 50% more likely to develop heart disease compared to females who do not go through early menopause.

Females who begin to menstruate (Menarche) very early or late are also at an increased risk of cardiovascular disease, so there is no doubt that the timing of changes in female-specific hormones plays a crucial role in cardiovascular risk.

Menopause

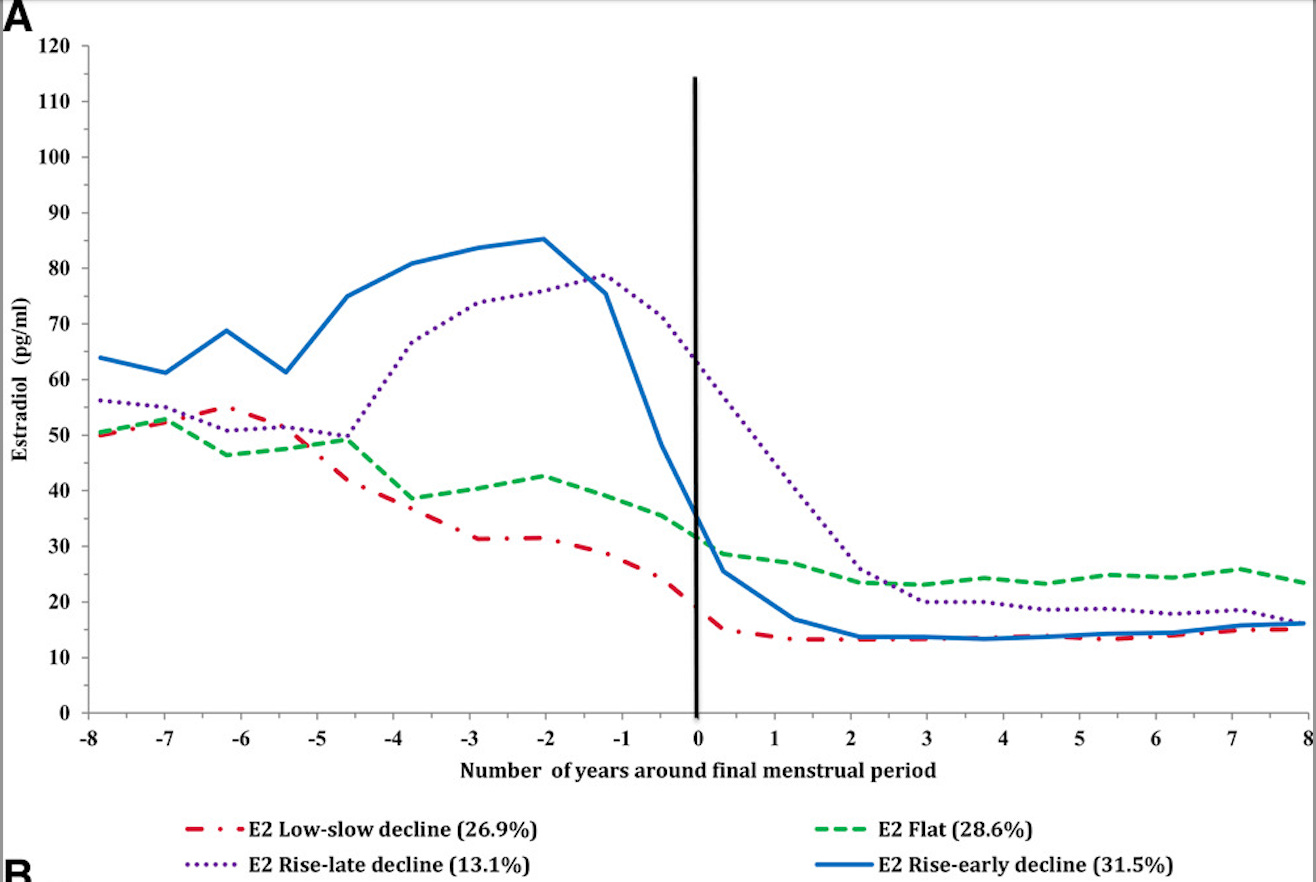

The cardinal feature of menopause is the abrupt loss of circulating oestrogen7.

Post-menopause, many other changes occur alongside the rise in LDL cholesterol.

Many of these also increase the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Post Menopause, several cardiometabolic risk factors worsen, including:

-

Reduced sleep quality

-

Increased visceral fat deposition

-

Worsening insulin resistance

-

Higher blood pressures

-

Lower HDL cholesterol

-

Mood changes - Depression

It would therefore seem unlikely that the increase in risk seen with early menopause is solely mediated through increases in LDL cholesterol but likely reflects the impact of a multifactorial change in risk factors.

If menopause is characterised by a sudden drop in oestrogen levels, the question is whether replacing female-specific hormones would reduce cardiovascular risk.

Hormone Replacement Therapy

The topic of hormone replacement therapy (HRT) is vast, and the decision to use HRT is dependent on many different variables, cardiovascular risk being only one of them.

I will focus primarily on cardiovascular risk, but even this topic is huge and equally controversial.

The Women’s Health Initiative (WHI) is the largest study ever conducted on hormone replacement therapy in post-menopausal females.

In general, females received combination HRT comprising conjugated equine estrogen and progesterone. Females who did not have a uterus received only conjugated equine estrogen.

The majority of the attention has always been on the combination group, which we will focus on here, given that most females currently considering HRT will be in that category.

From what we have covered so far, it would seem likely that using HRT would defer the onset of LDL cholesterol increases and decrease cardiovascular events.

After 13 years of follow-up in the WHI, there were a greater number of cardiovascular events in the combination HRT arm compared to the placebo arm.

These events were mostly strokes8.

Not exactly what we would have expected.

However, like everything in life, the devil is in the details.

As with any trial, we can only apply the findings to the groups that were evaluated.

In the WHI, the average age of females at the start of the trial was 63 years of age, the majority of which had no symptoms, and almost half had smoked at some point in their lives.

This sample, then, is not exactly reflective of the majority of females who are considering HRT today.

In the WHI, the risk of a cardiovascular event increased the further a female was from the date of menopause, with some of the females in the trial already being 10 years post-menopause.

This does not even take into consideration the likely several years of perimenopause that preceded the onset of menopause. The average age of menopause is 51.

Several follow-up studies evaluating cardiovascular risk in younger females much closer to the onset of menopause have shown clear benefits with the use of HRT, including9:

-

Lower LDL cholesterol

-

Higher HDL cholesterol

-

Less carotid intima-media thickening progression

-

No signal of increased events.

A trial of similar size as the WHI will unlikely ever be repeated, and we must therefore use data from smaller, shorter trials to make decisions today.

It seems very likely, however, that for younger females, particularly with symptoms of menopause and perimenopause, the use of HRT is likely to be, at minimum, safe from a cardiovascular perspective and likely to be beneficial.

For females with documented coronary artery disease, however, we must tread more carefully.

Females in this category require a very nuanced consideration around the risks and benefits of cardiovascular disease risk and also the benefits that come with HRT.

What is clear is that there is no one-size-fits-all approach here.

Particularly given the evolution in the types of HRT that are available.

This is a complex area and requires consultation with a clinician with domain expertise.

Not all clinicians have that domain-specific expertise, so when considering HRT make sure you are getting advice and input from the most qualified source you can find.

Maas AH, Appelman YE. Gender differences in coronary heart disease. Neth Heart J. 2010 Dec;18(12):598-602. doi: 10.1007/s12471-010-0841-y. PMID: 21301622; PMCID: PMC3018605.

https://www.womenshealth.gov/node/1374

Risk of Premature Cardiovascular Disease vs the Number of Premature Cardiovascular Events. JAMA Cardiol. 2016;1(4):492-494.

Maas AH, Appelman YE. Gender differences in coronary heart disease. Neth Heart J. 2010 Dec;18(12):598-602. doi: 10.1007/s12471-010-0841-y. PMID: 21301622; PMCID: PMC3018605.

Women Living with Familial Hypercholesterolemia: Challenges and Considerations Surrounding Their Care. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2020 Aug 20;22(10):60.

Bachorik PS, Lovejoy KL, Carroll MD, Johnson CL. Apolipoprotein B and AI distributions in the United States, 1988-1991: results of the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey III (NHANES III). Clin Chem. 1997 Dec;43(12):2364-78. PMID: 9439456.

American Heart Association Prevention Science Committee of the Council on Epidemiology and Prevention; and Council on Cardiovascular and Stroke Nursing. Menopause Transition and Cardiovascular Disease Risk: Implications for Timing of Early Prevention: A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020 Dec 22;142(25):e506-e532.

What the Women's Health Initiative has taught us about menopausal hormone therapy. Clin Cardiol. 2018 Feb;41(2):247-252.

Chester RC, Kling JM, Manson JE. What the Women's Health Initiative has taught us about menopausal hormone therapy. Clin Cardiol. 2018 Feb;41(2):247-252. doi: 10.1002/clc.22891. Epub 2018 Mar 1. PMID: 29493798; PMCID: PMC6490107.