Why You Need To Check Your Lp(a) If You Have A Family History Of Heart Disease

Cardiovascular disease accounts for 35% of all adult deaths in the developed world.

90% of the risk factors responsible for early heart disease have been described.

There are others we do not see or do not measure.

Lp(a) is one of them.

Knowing your Lp(a) level is crucial to understanding your cardiovascular risk.

I spend my days thinking about cardiovascular risk. When I hear a story like:

“My Dad had a heart attack at 50, and he was a nonsmoker”, or

“All my Uncles on my mother’s side had heart attacks in their 40s.”

I immediately think Lp(a).

But you probably haven’t heard of Lp(a). The problem is, neither have most doctors.

That would be ok if an elevated Lp(a) were a rare finding.

Elevated Lp(a) levels affect up to 10 - 20% of the population. That is up to 1 in 5 people.

Raised Lp(a) is the most common genetic cholesterol disorder. Most will have heard of Familial Hyperlipidemia (FH), a genetically elevated cholesterol disorder, but this has a frequency of only 1:200 to 1:300 people. Not rare. But nowhere near as common as a high Lp(a).

Although Lp(a) is rarely tested, it has been extensively researched. I will attempt to provide a summary of the highlights, but a full deep dive is beyond the scope of this article.

Cholesterol terminology can be confusing, but I will try to keep things simple.

First off, pronunciation. It’s ‘L. P. Little A’. Also known as Lipoprotein a.

Cholesterol is a practical everyday term, but to understand Lp(a), we need to be more precise.

Cholesterol is a fat (Lipid) carried in the bloodstream by a spherical structure made of protein. The combination creates a lipoprotein particle. Think of a protein tennis ball with fat droplets inside.

Lipoprotein = Lipid + Protein.

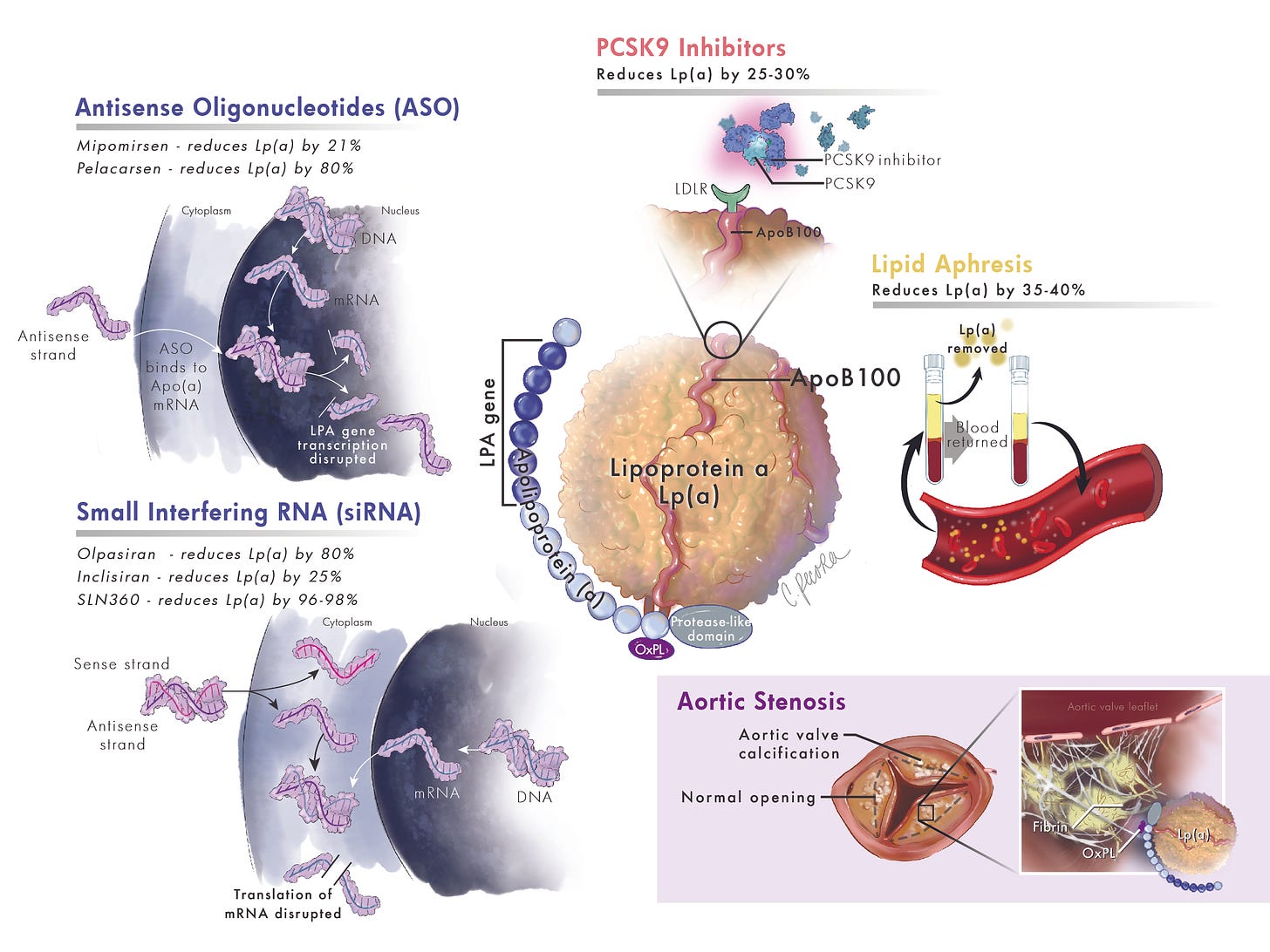

Lp(a) = Lipid + Protein + Lp(a) Tail.

The standard lipoprotein has a single APOB attached, but some will have a unique Lp(a) tail called a Kringle repeat. The word Kringle comes from its similarity to the Danish pastry with the same name.

This tail and its configuration significantly affect a person’s risk of coronary artery disease (atherosclerosis). The different tail structures result in different patient risk characteristics.

The main takeaway is that excess Lp(a) concentrations increase a person’s risk of early cardiovascular disease.

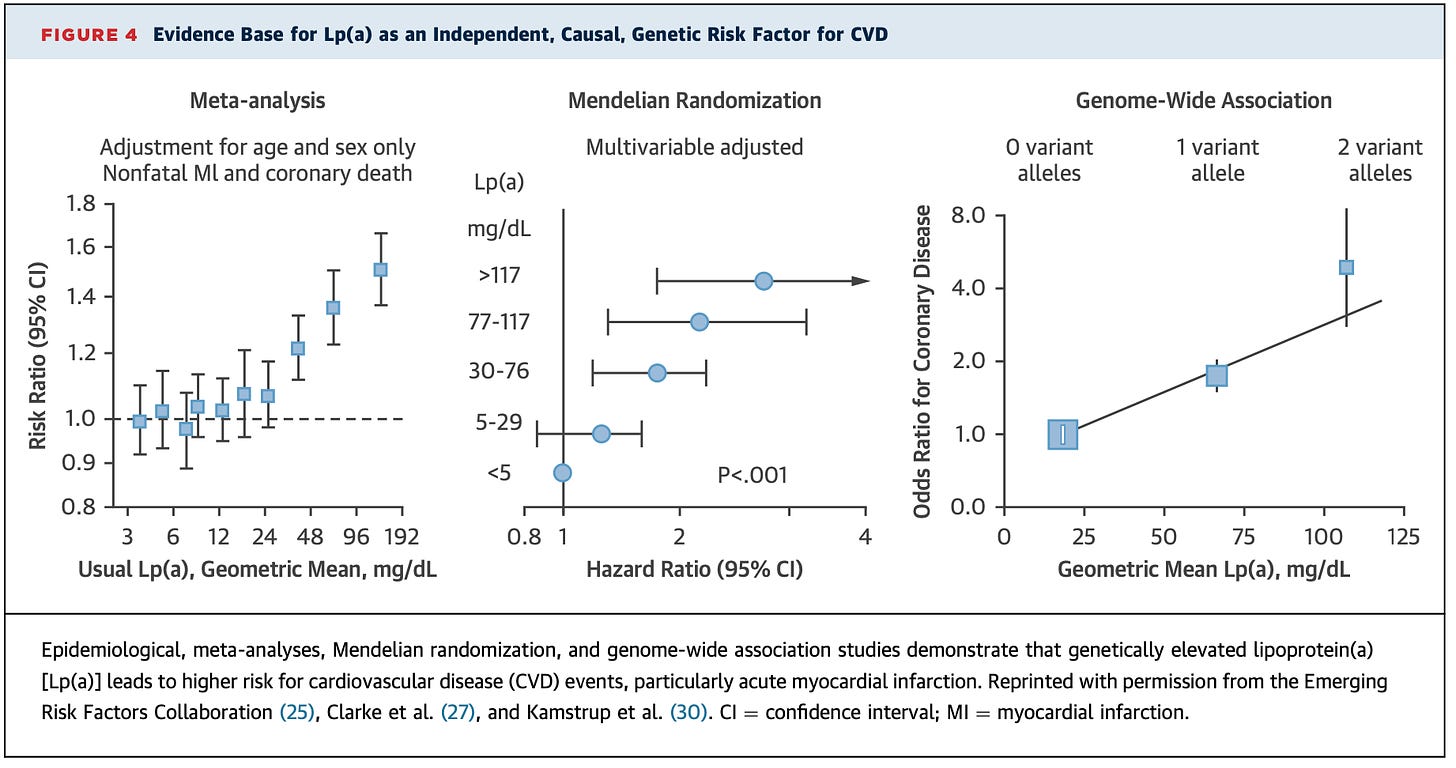

By how much? The answer, as always is, it depends. Multiple studies using a variety of different methods have shown that compared to those with normal levels of Lp(a), those with significantly elevated Lp(a) have a higher risk of:

A. Having coronary artery disease earlier in life.

B. Having a heart attack earlier in life.

If that last sentence confused you, please go back and reread it.

Having a risk factor (Lp(a)) is not the same as having the disease (atherosclerosis), which is not the same as having an event (heart attack or stroke).

The totality of the literature indicates that the more Lp(a) gene variants and the higher the number of particles you have, the greater the risk.

Guidelines suggest that everyone should have Lp(a) levels checked at least once in their lifetime. The reality is that few people have their levels checked.

Elevated Lp(a) levels are genetically determined, so if you have an early family history of heart disease, this is a must-do risk marker. There is solid evidence that levels stay the same throughout life, so this test need only ever be done once.

It’s not just coronary artery disease we need to think about.

Although Lp(a) is causal of early coronary artery disease, it is also related to early aortic valve calcification, stroke, peripheral valve disease and heart failure.

Traditionally Lp(a) levels >50mg/dl or >125nmol/L have been associated with the most significant increase in cardiovascular risk. However, even levels >30mg/dl or >75nmol/l have been associated with increased cardiovascular risk. Most labs will use the mg/dl unit of measurement, but the evidence is mounting that the nmol/L unit of measure is the better approximation of risk.

Approved Treatments

As of 2022, there are no approved treatments for those with an elevated Lp(a). This is partly why Lp(a) has not been routinely tested in clinical practice. It does not mean that steps cannot be taken to reduce a person’s future risk.

Therapies to reduce Lp(a) are under investigation. Antisense oligonucleotides such as Pelacarsen have demonstrated 80% reductions in Lp(a) levels. Still, we await the phase 3 outcome trial results to see if it reduces Lp(a) levels and events (Heart Attacks, Strokes etc.) in those at very high risk.

Small interfering RNA therapies have also shown reductions in Lp(a) concentrations of 80 to over 90% but are at an earlier stage of development. Currently available treatments, including PCSK9 inhibitors and Inclisiran, have shown moderate reductions in Lp(a) levels. Meta-analysis have suggested that there may be modest reductions in events with PCSK9 treatments, but to date, no randomised controlled trials have been conducted.

Statin therapy has no meaningful effect on Lp(a) concentrations and may even modestly increase levels. However, statin therapy can significantly reduce APOB/LDL-C concentrations that are not bound to Lp(a). By doing so, cardiovascular risk is reduced, and studies suggest that with an adequate LDL-C or APOB reduction, the added risk of a higher Lp(a) can be mitigated.

Bottom line. Do not stop your statin therapy based on a remote possibility of raising Lp(a). Additionally, considering a lower target, LDL-C/APOB might be necessary to offset risk. A 1 mmol/l reduction in LDL-C may be enough to offset the risk of every 100mg/dl increase in Lp(a).

Main Takeaways:

-

Everyone should have an Lp(a) level checked at least once.

-

If you have a family history of early cardiovascular disease. See rule 1.

-

If you have an elevated Lp(a), think about more aggressive targets for APOB & LDL-C.

-

In the absence of approved therapies for Lp(a) lowering, there may be a role for existing treatments such as PCSK9 inhibitors and Inclisiran.

-

All adult blood relatives of those with an elevated Lp(a) should be evaluated. See rule 1.

-

Novel therapies with randomised outcome data are coming soon (hopefully!).

Until approved therapies are available, it’s about being as detail-oriented as possible with traditional cardiovascular risk factors and taking the advice of my lawyer friends:

“You need to cross your T’s, dot your i’s and…… dot your lower case j’s.”